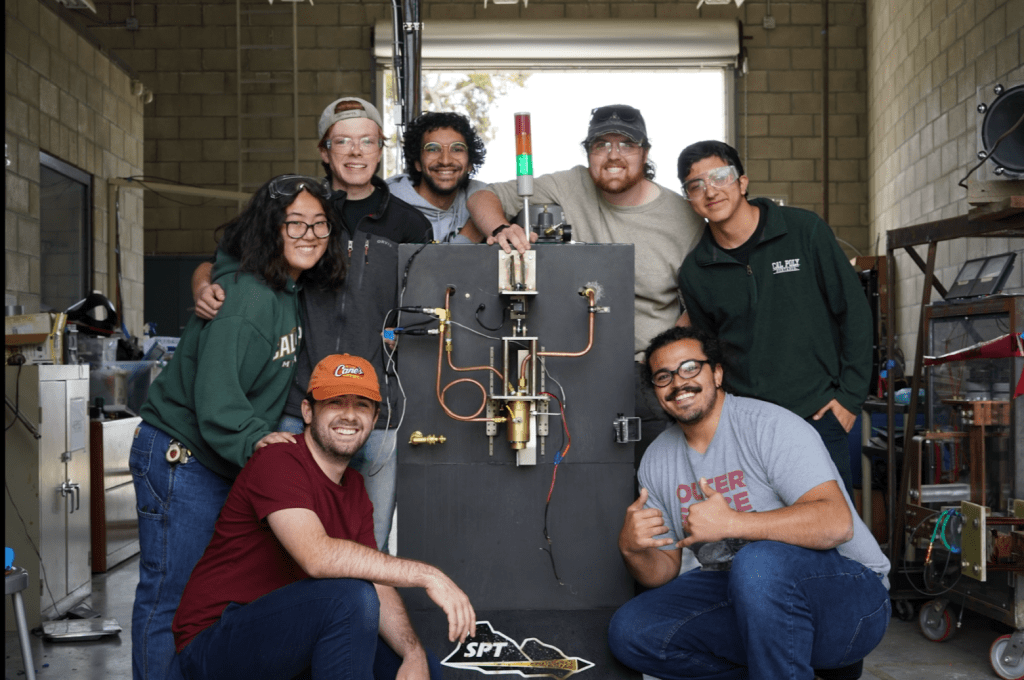

This year, I had the privilege to work alongside some talented engineers at CalPoly to develop the first liquid rocket engine that a club at our school had ever produced. The idea had started just one year ago amongst a couple of us, but it quickly gained interest and traction among students, allowing us to produce our first rocket engine and grow into a full club.

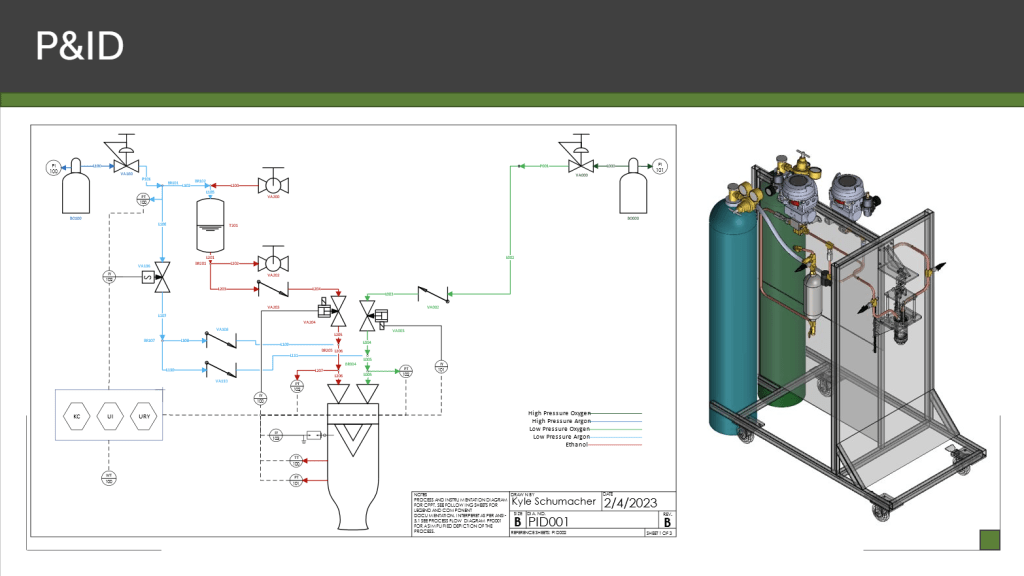

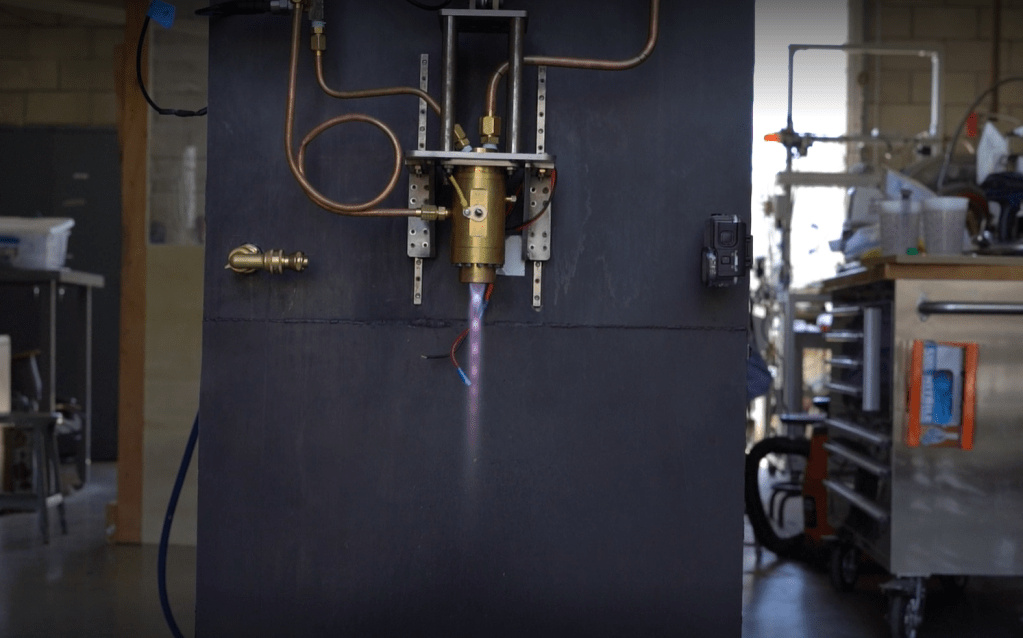

We called it the MK1 Demonstrator, which allowed us to demonstrate our capabilities to produce a small-scale rocket engine. Our primary propellants were GOx (Gaseous Oxygen) and Ethanol, one of the fastest and easiest to get a functional system working. When choosing propellants, many factors go into that trade, but on this scale, the ISP (efficiency) is similar for the most common fuels, and we had readily accessible gaseous oxygen. We additionally used argon for our pressurization fluid as we had free access to the otherwise uncommon gas (typically heavier and more expensive than nitrogen).

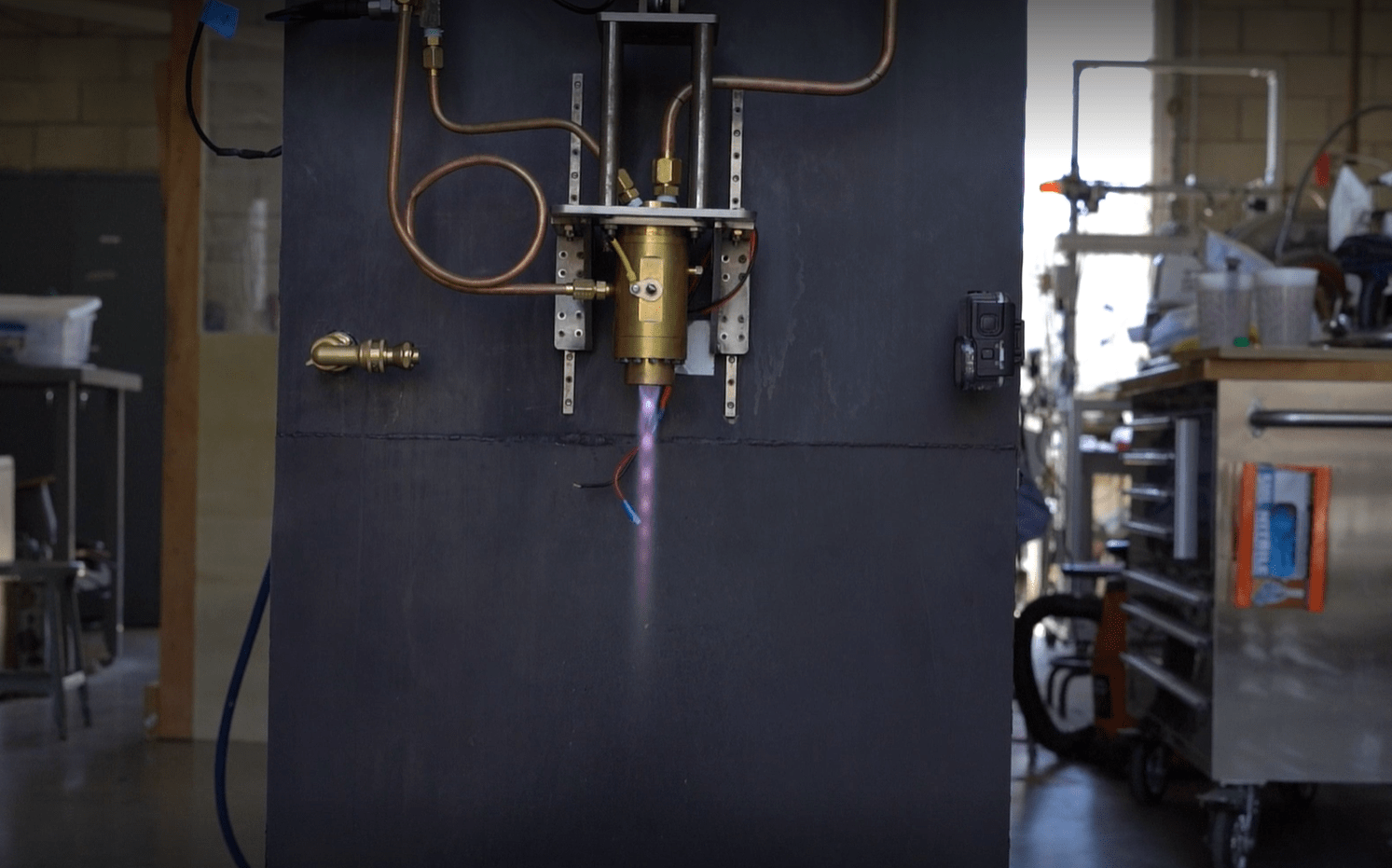

It took a couple cold flows and hot fires to eventually get the system working reliably. Our first hot fire was more of a “flame thrower” as the oxygen regulator was not providing the flow rates expected. We iterated the ethanol feed pressure to find the desired OF (Oxygen to Fuel) ratio and get stable combustion. Additionally, we were having difficulty trying to get our initial ignition source (custom spark-plug) to reliably ignite the fluid in the chamber. We then tried a glow plug, but found they heavily relied on position in the chamber and ended up burning up a couple in this process. We finally landed on sticking an average sparkler up the nozzle and timing all events almost perfectly. An average sparkler will last for around 30 seconds, but I found through testing that a sparkler in a pure oxygen environment lasts about 25 ms before it is completely ignited. By reviewing high-speed footage, I was able to back-out the correct timing for all valves and ignition to get reliable ignition everytime.

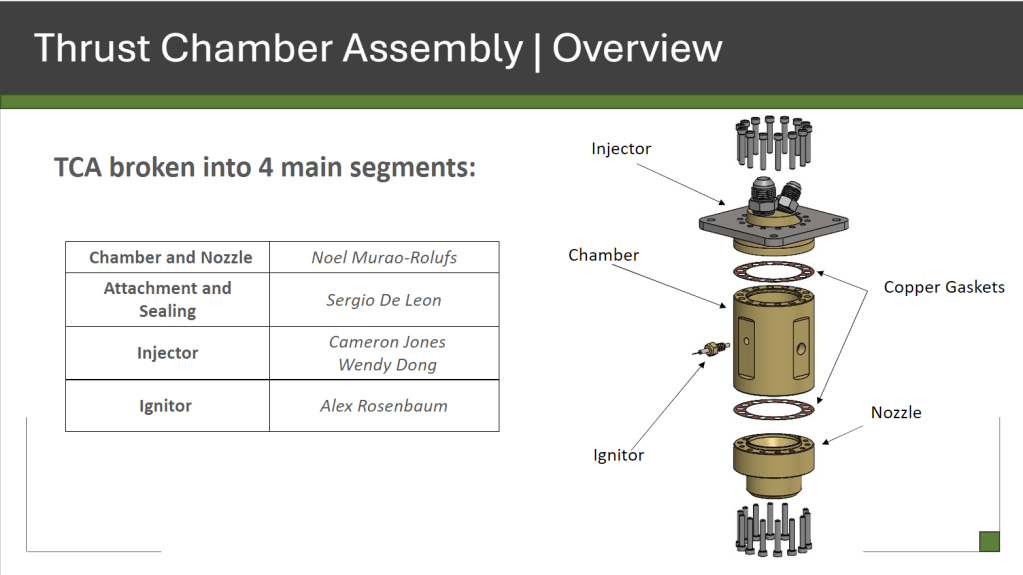

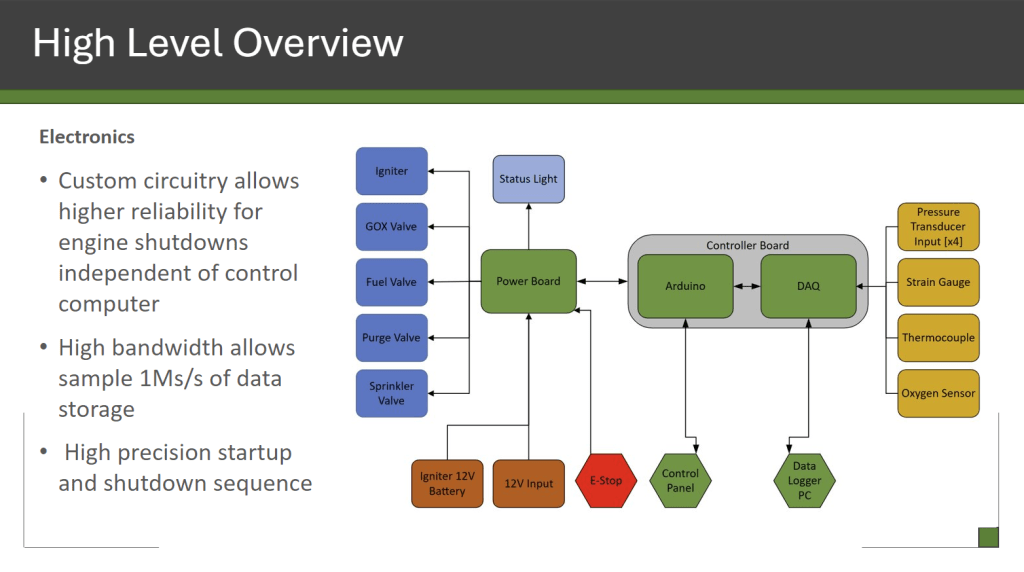

After founding the club, my main role was as the fluid systems lead and electronics lead. This included sizing all feedline components (regulators, tanks, tubes, fittings, etc) to support our specific rocket engine parameters. For electronics, we built up a DAQ that was integrated into the flight controller running on a simple Teensy 4.1. Using this system, we could assign “red-lines” to the system so that it would perform automated shutdowns if any of our sensor readings detected an anomaly. My roles then changed to chief engineer of the MK1 system, which meant making sure all parts of the engine were designed, manufactured, and tested to our guidelines. It also meant understanding all parts of the engine so that each subsystem could be integrated together.

Overall, I had a lot of fun working on this project and learned a lot about propulsion along the way. I’m excited to see the future of this club and the other cool projects we have coming up that are influenced by our lessons learned on this project.

Some design slides for more technical details: